Understanding Internal Dysfunction and the Role of Stecco Fascial Manipulation®

When we think of pain or dysfunction in the body, we often associate it with injuries to muscles, joints, or nerves. However, what if the source of your discomfort isn’t just mechanical? What if persistent pain, digestive issues, or pelvic discomfort were linked to a lesser-known but critically important system in the body—the fascia?

This is where Stecco Fascial Manipulation® stands out, especially in addressing internal dysfunction.

What Is Internal Dysfunction?

Internal dysfunction refers to problems that originate from or affect the viscera—your internal organs. This can include:

Gastrointestinal issues (bloating, constipation, reflux)

Urinary problems (urgency, frequency, incontinence)

Menstrual or pelvic pain

Breathing difficulties (tight diaphragm, shallow breathing)

Chronic fatigue or systemic tension

These symptoms often don’t show up clearly on imaging, and they’re frequently misattributed to stress, aging, or psychosomatic causes.

But there's often a missing link—the fascia.

Fascia: The Body's Hidden Communication Network

Fascia is a dense connective tissue that envelops and interconnects muscles, nerves, vessels, and internal organs. It plays a major role in posture, movement, and pain perception. When fascia becomes restricted due to trauma, surgery, inflammation, poor posture, or emotional stress, it can create tension patterns that pull on surrounding tissues—including the fascial connections around organs.

These restrictions can lead to:

Visceral discomfort

Referred musculoskeletal pain

Autonomic nervous system dysregulation

Reduced organ mobility and function

How Stecco Fascial Manipulation® Addresses Internal Dysfunction

Stecco Fascial Manipulation® is a science-based, hands-on therapy developed by Luigi Stecco and expanded by Drs. Carla and Antonio Stecco. It focuses on restoring the glide and elasticity of fascial tissues, using precise palpation and targeted manual release techniques.

Key Concepts:

Centers of Coordination (CCs): Points where muscle forces converge and are regulated by fascial tension.

Centers of Fusion (CFs): Deeper fascial points related to organ function and autonomic regulation.

Myofascial Sequences: Chains of muscles and fascia that work together during functional movement.

In cases of internal dysfunction, trained practitioners evaluate both somatic (muscle/fascial) and visceral (organ/fascial) patterns. Treatment targets areas of densification (thickened fascia) that may be restricting internal structures, thus improving circulation, nerve supply, and organ mobility.

Clinical Applications

Many patients are surprised to find that seemingly unrelated symptoms—like chronic lower back pain and constipation—are actually connected through fascial pathways. Some examples of conditions that may benefit from Stecco Fascial Manipulation® for internal dysfunction include:

Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS), Bloating

Interstitial Cystitis

Pelvic Floor Dysfunction and incontinence

Gastrointestinal Reflux Disease (GERD)

Post-surgical adhesions

Chronic pelvic pain

By reducing fascial restrictions, patients often experience not only decreased pain but also improved organ function, better posture, and a deeper sense of well-being.

A Whole-Body, Evidence-Based Approach

What makes Stecco Fascial Manipulation® unique is its integrative and anatomical precision. Rather than chasing symptoms, practitioners analyze full-body movement patterns, medical history, and tissue texture to identify the root causes of dysfunction. The therapy is supported by anatomical dissections and clinical research, particularly from the Stecco Fascial Manipulation Institute.

Conclusion: Treating More Than Just Muscles

Internal dysfunction doesn’t always require medication or surgery. Sometimes, the key lies in restoring balance to your fascial system—especially where it interacts with your organs. Stecco Fascial Manipulation® offers a powerful, precise method to address these deeper, more complex dysfunctions in a way that is both scientific and deeply human.

If you've been living with unexplained discomfort, chronic pain, or internal symptoms that don’t respond to conventional treatment, consider consulting a certified Fascial Manipulation practitioner. Your fascia may hold the key to healing.

Would you like this article formatted for web use or turned into a downloadable brochure? I can also create supporting images or diagrams to illustrate how fascial lines connect to organ systems.

Ready to Feel Connected Again?

If you're struggling with persistent symptoms and haven’t found answers, Stecco Fascial Manipulation® Therapy at AllConnected Physical Therapy may be the solution you’ve been looking for.

📍 Visit us in Naperville, IL

📞 Call: 847-732-2336

📅 Book an Appointment

Let’s reconnect your body from the inside out.

Understanding Fascial Manipulation: How It Helps Pain and Movement

Testing this cuz idk

Ben Grotenhuis, PT, CMTPT, FAAOMPT

Fascial Manipulation® by Stecco is a scientifically backed, hands-on therapy that targets the body’s—fascial tissue—an intricate web of connective tissue that surrounds and links together our muscles, tendons, bones, nerves, blood vessels, and even internal organs.

Over time, factors like overuse, injury (both recent and old), inflammation, or periods of immobility can interfere with the natural movement between these fascial layers. This leads to areas of thickened, stiffened tissue—known as “densifications”—which can be felt during examination and have even been shown on ultrasound to be physically thicker (Stecco et al., 2014; Luomala et al., 2014). These densified areas can disrupt how muscles and tendons function, altering muscle recruitment patterns and joint mechanics, ultimately resulting in pain or injury.

The body is great at adapting, often changing the way we walk, lift, or move to compensate for fascial restrictions. But these adjustments can eventually lead to pain or dysfunction in other areas. Fascial Manipulation® aims to restore the natural glide and slide of fascial tissue, helping the body move more freely and function at its best.

What Is Fascia and What Is Its Function?

The fascial system is more than just a type of connective tissue—it operates as an integrated system. It connects different parts of the body, senses and communicates changes, transmits mechanical forces, offers protection, and creates the environment necessary for the body to function as a cohesive whole.

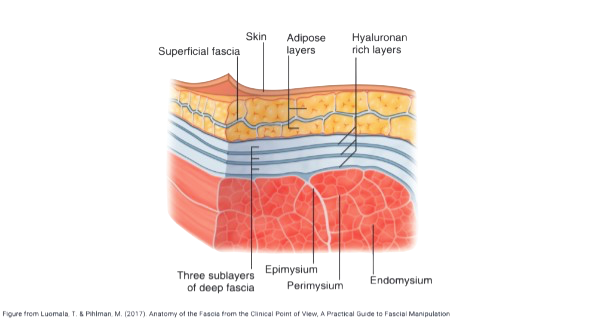

Types of Fascia

Several distinct types of fascia have been identified, including superficial fascia. This type is composed of loosely arranged, interwoven collagen and elastic fibers, with elastic fibers being more abundant. As a result, superficial fascia is more pliable than other fascia types. Located just beneath the skin, it separates the two layers of subcutaneous adipose tissue. Its primary role is to anchor the skin while allowing it to stretch and move in multiple directions. With age, the superficial fascia gradually loses its elasticity, contributing to reduced skin tone and the formation of wrinkles. Additionally, it serves as a conduit for nerves, lymphatic drainage, and blood vessels, protecting these vital structures from excessive compression or stretching. By creating a layer between the skin and underlying muscles, the superficial fascia facilitates independent movement between them.

Deep fascia is a dense connective tissue structure that envelops and interconnects muscles, muscle groups, bones, nerves, and internal organs. It is also considered an integral component of the nervous system due to its high concentration of nerve endings and sensory receptors. These features make deep fascia highly responsive to changes in tissue tension, allowing it to detect even subtle movements throughout the body. By sensing variations in fascial tension, it not only perceives movement (proprioception) but also contributes to the coordination and execution of movement patterns.

Deep fascia provides a smooth, gliding interface for muscles, facilitating efficient and coordinated movement. Under normal conditions, approximately 30–40% of muscular forces are transmitted through the fascia from one body part (e.g., the fingers and wrist) to the next (e.g., the elbow), continuing along the kinetic chain. This force transmission occurs both laterally and longitudinally, allowing muscles to influence adjacent or functionally connected structures. When fascial function is impaired, it can disrupt normal movement patterns and alter the transmission of forces through muscle tissues. These disruptions also affect the function of sensory receptors critical to motor control and muscle recruitment. Over time, such changes can lead to compensatory movement strategies, increasing the risk of pain, dysfunction, and injury throughout the body. This explains how dysfunction or restriction in one area (e.g., the hip) can influence another (e.g., the ankle or shoulder).

Langevin et al. (2009, 2011), using ultrasound imaging, observed a 25% increase in fascial thickness in the lumbar region of individuals with chronic low back pain compared to those without pain. In a subsequent study in 2011, the same researchers found that shear strain within the lumbar fascia was 20% lower in subjects with chronic low back pain, indicating compromised connective tissue function. Supporting these findings, Stecco et al. (2014) used similar imaging techniques and discovered increased fascial thickness in the anterior neck muscles of patients with chronic neck pain compared to a control group.

Healthy Fascia that Glides Easily vs Adhered and Dysfunctional Fascia with Limited Gliding

Healthy Fascial Tissues vs. Adhered Fascial Tissues

Healthy Fascia Tissue

💧 Well-hydrated and pliable

🔄 Smooth gliding between fascial layers

🤸♂️ Supports full, pain-free mobility

🧠 Communicates efficiently with the nervous system

🩺 Supports optimal function of muscles, nerves, and organs

🌬️ Assists circulation, lymphatic flow, and breathing mechanics

Adhered/ Dysfunctional Fascia

🪨 Dehydrated or densified

⚠️ Restricted movement between fascial planes

🚫 Leads to stiffness, tightness, and pain

📉 Disrupted sensory input and motor control

💢 May contribute to compensations, imbalances, and dysfunctions

Visceral Fascia serves to protect and support the internal organs, anchoring them in place within the body. For example:

The diaphragmatic fascia influences the lungs and digestive organs.

The pelvic fascia connects to the reproductive and urinary organs.

The visceral fascia is composed of two main layers: the insertional fascia, which connects internal organs to the musculoskeletal system, and the investing fascia, which envelops individual organs and facilitates peristalsis and neural communication between organs and their surrounding structures.

Healthy visceral fascia plays a vital role in supporting organ function. It maintains a delicate balance between tension and flexibility, allowing internal organs to move freely and carry out essential processes like digestion, elimination, and reproduction. When this balance is disrupted—due to trauma, inflammation, or infection—fascial restrictions can limit organ mobility. At the same time, tight fascia in the abdomen or back can lead to symptoms such as acid reflux, bloating, constipation, menstrual pain, or urinary incontinence. Conversely, overly lax fascia may not provide enough support, increasing the risk of organ prolapse. In either case, impaired fascial function can contribute to discomfort, pain, and widespread dysfunction in the body.

In Summary

Both superficial fascia (just under the skin) and deep fascia (surrounding muscles, bones, and organs) form a continuous, interconnected web. This web not only stabilizes and supports structures but also transmits mechanical tension throughout the body — including to and from internal organs.

Both superficial and deep fascia in the body can be treated using manual techniques, either directly or indirectly, and this treatment can also influence dysfunctions of internal organs.

How Does Fascial Manipulation Work?

The fascial system is a continuous, three-dimensional, interconnected web that envelops and supports all muscles, bones, and organs. Although it may appear as a single sheet, fascia is composed of multiple layers separated by a lubricating substance known as hyaluronan. Under normal conditions, hyaluronan allows these layers to glide smoothly over one another. However, in response to trauma, surgery, inflammation, or prolonged immobilization, hyaluronan can become more viscous and gel-like, reducing its lubricating ability. This diminished glide leads to the formation of densifications—localized areas of thickened, stiffened fascia that can restrict movement and cause pain. In an effort to maintain mobility, the body often compensates for these restrictions, which can result in pain or dysfunction in other regions. Fortunately, fascial manipulation techniques can target these densifications both locally and globally, helping to restore the normal consistency of hyaluronan, improve fascial glide, and alleviate associated discomfort and dysfunction.

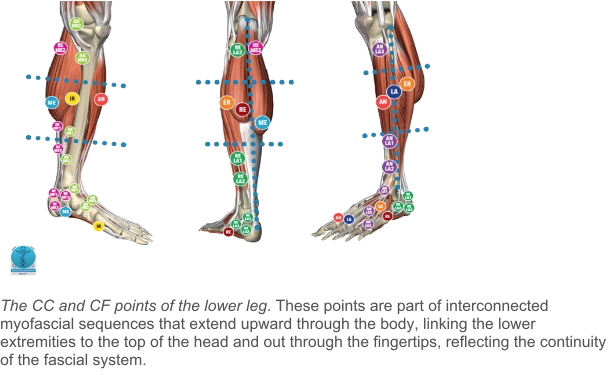

Dysfunctions or densifications in one area can lead to compensatory issues elsewhere. Fascial manipulation, particularly the Stecco Method® utilizes detailed anatomical maps to identify and treat specific points within the fascial systems with the goal of restoring balance and function throughout the body.

These maps highlight:

Centers of Coordination (CC): Points that coordinate movement in a specific direction.

Centers of Fusion (CF): Points where multiple movements converge

These points are organized along myofascial sequences, which are chains of muscles and fascia that work together to produce movement.

For example. In the lower limb, specific CC and CF points are identified to address movement dysfunctions. For instance, treating a densified point in the thigh’s fascia can alleviate pain in the knee or ankle due to the interconnected nature of the fascial system.

How Does It Feel? Understanding Fascia and Pain.

Because the superficial fascia lies just beneath the skin, it is particularly responsive to gentle manual techniques that involve broad, light friction across the surface of the subcutaneous tissue. This gradual, gentle pressure encourages the reorganization of focal adhesions and the macromolecular architecture within the fascia, helping to restore its normal, healthy function. Research by Carla Stecco et al. (2016) has shown that dysfunctions in the lymphatic system—such as swelling, impaired superficial venous drainage, and disrupted thermoregulation—are often closely associated with abnormalities in the superficial fascia. These dysfunctions can also contribute to altered mechanical coordination, impaired proprioception, and compromised balance.

Myofascial pain and muscle cramps are often associated with dysfunction in the deep fascia. Due to its dense connective tissue structure, effective treatment requires techniques capable of reaching the underlying muscle surfaces. Stecco Fascial Manipulation® is one such method, involving the precise identification of Centers of Coordination (CC) and Centers of Fusion (CF). Targeted manual deep friction is applied to these points to restore fascial glide, improve biomechanical alignment, and alleviate pain and dysfunction.

Dysfunctional movement patterns—often reflective of fascial system imbalances—are typically identified during a physical therapy evaluation through range of motion and strength assessments. Areas of fascial densification, or localized tissue thickening, are discovered through skilled palpation. These regions are generally more tender than surrounding tissue and may provoke sharp or unusual sensations. Notably, densifications are frequently located at a distance from the patient’s reported area of pain. However, they reliably correspond with impaired movement, reduced strength, and functional limitations, underscoring the interconnected nature of the fascial system.

After a full-body assessment, these fascial points are treated through manual manipulation directly on the skin, typically lasting 2 to 5 minutes. This process usually leads to a noticeable reduction in tenderness at the treated site. The therapist then reassesses movement to evaluate improvements in mobility and pain reduction. Patients are advised that treated areas may feel sore or tender for 24 to 48 hours, likely due to a localized inflammatory response. During follow-up sessions, palpation of these areas often reveals reduced tenderness and less density. As a result, movement patterns and strength tend to improve as pain and dysfunction diminish.

Deep Fascia, Pain, and the Role of Stecco Fascial Manipulation®

Myofascial pain and muscle cramps are frequently linked to dysfunction in the deep fascia. This dense connective tissue layer envelops muscles and bones, helping coordinate movement and transmit muscular force. When the deep fascia becomes stiff or densified, it can restrict mobility and cause pain—both locally and in distant areas.

Stecco Fascial Manipulation® is a precise manual therapy technique that targets these dysfunctions. It begins with identifying specific points called Centers of Coordination (CC) and Centers of Fusion (CF), which correspond to lines of muscular force transmission. Deep, focused manual friction is applied directly to the skin over these points, helping to restore the fascia’s gliding capacity, improve alignment, and reduce symptoms.

How Treatment Can Help Restore Fascial Balance and Support Organ Function

By restoring healthy mobility and tone to the visceral fascia and the deep fascia of the abdominal and back walls, The Stecco Fascial Manipulation® treatment method can help:

Improve organ mobility and coordination

Alleviate symptoms such as bloating, acid reflux, and constipation

Relieve menstrual pain and pelvic discomfort

Support bladder control and reduce urinary incontinence

Enhance overall comfort, movement, and internal balance

Each session is personalized based on your unique pattern of fascial restriction. The goal is to restore natural motion and support, allowing your organs to function freely and without undue strain.

Physical Therapy Evaluation and Treatment Process

During an evaluation, therapists assess range of motion, movement quality, and strength to detect abnormal patterns that may indicate fascial restrictions. Through skilled palpation, areas of fascial densification—regions of thickened, stiff tissue—are identified. These spots are often more tender than surrounding areas and may produce unusual or sharp sensations upon touch. Interestingly, they often lie far from where the patient reports pain, highlighting the fascial system’s interconnected nature.

Treatment typically involves 2 to 5 minutes of manual manipulation per point. This usually leads to a noticeable reduction in tenderness at the treated site. The therapist then reassesses movement and pain levels to gauge progress. Mild soreness may occur for 24–48 hours following treatment, likely due to a localized inflammatory response.

Over subsequent sessions, these densifications often soften, and sensitivity decreases. As a result, patients typically experience improved strength, movement efficiency, and reduced pain.

Stecco Fascial Manipulation® is effective in treating a wide range of conditions related to dysfunction in the fascial system. These typically include:

Musculoskeletal Conditions

Chronic neck or back pain

Shoulder impingement or rotator cuff syndrome

Hip pain or impingement

Knee pain, including patellofemoral syndrome

Plantar fasciitis and foot pain

Achilles tendinopathy

Sciatica and piriformis syndrome

Carpal tunnel syndrome

Tennis or golfer’s elbow

TMJ (temporomandibular joint) disorders

Lasting pain and limitations after shoulder, knee and hip replacement surgery

Myofascial and Postural Dysfunctions

Myofascial pain syndrome

Recurrent muscle strains

Muscle cramps and spasms

Postural imbalance or asymmetry

Limited range of motion (ROM)

Compensatory movement patterns

Visceral-Related Symptoms

Reflux or bloating

Constipation or irritable bowel symptoms

Menstrual pain or pelvic discomfort

Urinary incontinence

Neurological and Referred Pain

Tension headaches

Thoracic outlet syndrome

Nerve entrapment symptoms (numbness, tingling, shooting pain)

Morton’s syndrome (neuroma) causing foot pain

Curious if Fascial Manipulation could help you?

Give us a call at 847-732-2336 or schedule an evaluation at AllConnected Physical Therapy in Naperville. We’ll take a whole-body approach to help you move and feel better—because yes, it’s all connected.

Ben Grotenhuis, PT, CMTPT, FAAOMPT, FMID

Currently one of only a few clinicians in Illinois trained in the evaluation and treatment of fascial dysfunction using the Stecco Method of Fascial Manipulation® (level I-IV)

References

Stecco, C., et al. (2014). “Investigation of the mechanical properties of the human crural fascia and their possible clinical implications.” Surgical and Radiologic Anatomy 36(1): 25-32.

Luomala, T., et al. (2014). “Case study: Could ultrasound and elastography visualized densified areas inside the deep fascia?”; J Bodyw Mov Ther 18(3): 462-468.

Langevin, H. M., et al. (2009). “Ultrasound evidence of altered lumbar connective tissue structure in human subjects with chronic low back pain.” BMC Musculoskelet Disord 10: 151-151.

Langevin, H. M., et al. (2011). “Reduced thoracolumbar fascia shear strain in human chronic low back pain.” BMC Musculoskelet Disord 12: 203.

Stecco A et al. (2011). “RMI study and clinical correlations of ankle retinacula damage and outcomes of ankle sprains.“ Surg Radiol Anat 33(10): 881-90

Stecco, A., et al. (2014). “Ultrasonography in myofascial neck pain: randomized clinical trial for diagnosis and follow-up.” Surg Radiol Anat 36(3): 243-253.

Pedrelli, A., et al. (2009). “Treating patellar tendinopathy with Fascial Manipulation.” J Bodyw Mov Ther 13(1): 73-80.

Picelli, A., et al. (2011). “Effects of myofascial technique in patients with subacute whiplash associated disorders: a pilot study.” Eur J Phys Rehabil Med 47(4): 561-568.